September 1st, 2022: see an updated revision.

Block-STM is a recently announced technology for accelerating smart-contract execution, emanating from the Diem project and matured by Aptos Labs. The acceleration approach interoperates with existing blockchains without requiring modification or adoption by miner/validator nodes, and can benefit any node independently when it validates transactions.

This post explains Block-STM in simple English accompanied with a running scenario.

Background

An approach pioneered in the Calvin 2012 and Bohm 2014 projects in the context of distributed databases is the foundation of much of what follows. The insightful idea in those projects is to simplify concurrency management by disseminating pre-ordered batches (akin to blocks) of transactions along with pre-estimates of their read- and write- sets. Every database partition can then autonomously execute transactions according to the block pre-order, each transaction waiting only for read dependencies on earlier transactions in the block. The first DiemVM parallel executor implements this approach but it relies on a static transaction analyzer to pre-estimate read/write-sets which is time consuming and can be inexact.

Another work by Dickerson et al. 2017 provides a link from traditional database concurrency to smart-contract parallelism. In that work, a consensus leader (or miner) pre-computes a parallel execution serialization by harnessing optimistic software transactional memory (STM) and disseminates the pre-execution scheduling guidelines to all validator nodes. A later work OptSmart 2021 adds read/write-set dependency tracking during pre-execution and disseminates this information to increase parallelism. Those approaches remove the reliance on static transaction analysis but require a leader to pre-execute blocks.

The Block-STM parallel executor combines the pre-ordered block idea with optimistic STM to enforce the block pre-order of transactions on-the-fly, completely removing the need to pre-disseminate an execution schedule or pre-compute transaction dependencies, while guaranteeing repeatability.

Technical Overview

Block-STM is a parallel execution engine for smart contracts, built around the principles of Software Transactional Memory. Transactions are grouped in blocks, each block containing a pre-ordered sequence of transactions TX1, TX2, …, TXn. Transactions consist of smart-contract code that reads and writes to shared memory and their execution results in a read-set and a write-set: the read-set consists of pairs, a memory location and the transaction that wrote it; the write-set consists of pairs, a memory location and a value, that the transaction would record if it became committed.

Block pre-order

A parallel execution of the block must yield the same deterministic outcome that preserves a block pre-order, namely, it results in exactly the same read/write sets as a sequential execution. If, in a sequential execution, TXk reads a value that TXj wrote, i.e., TXj is the highest transaction preceding TXk that writes to this particular memory location, we denote this by:

TXj → TXk

Running example

The following scenario will be used throughout this post to illustrate parallel execution strategies and their effects.

A block B consisting of ten transactions, TX1, TX2, ..., TX10,

with the following read/write dependencies:

TX1 → TX2 → TX3 → TX4

TX3 → TX6

TX3 → TX9

To illustrate execution timelines, we will assume a system with four parallel threads, and for simplicity, that each transaction takes exactly one time-unit to process.

If we knew the above block dependencies in advance, we could schedule an ideal execution of block B along the following time-steps:

1. parallel execution of TX1, TX5, TX7, TX8

2. parallel execution of TX2, TX10

3. parallel execution of TX3

4. parallel execution of TX4, TX6, TX9

Correctness

What if dependencies are not known in advance? A correct parallel execution must guarantee that all transactions indeed read the values adhering to the block dependencies. That is, when TXk reads from memory, it must obtain the value(s) written by TXj, TXj → TXk, if a dependency exists; or the initial value at that memory location when the block execution started, if none.

Block-STM ensures this while providing effective parallelism. It employs an optimistic approach, executing transactions greedily and optimistically in parallel and then validating. Validation of TXk re-reads the read-set of TXk and compares against the original read-set that TXk obtained in its latest execution. If the comparison fails, TXk aborts and re-executes.

Correct optimism revolves around maintaining two principles:

- READLAST(k): Whenever TXk executes (speculatively), a read by TXk obtains the value recorded so far by the highest transaction TXj preceding it, i.e., where j < k. Higher transactions TXl, where l > k, do not interfere with TXk.

- VALIDAFTER(j, k): For every j,k, such that j < k, a validation of TXk’s read-set is performed after TXj executes (or re-executes).

Jointly, these two principles suffice to guarantee both safety and liveness no matter how transactions are scheduled. Safety follows because a TXk gets validated after all TXj, j < k, are finalized. Liveness follows by induction. Initially transaction 1 is guaranteed to pass read-set validation successfully and not require re-execution. After all transactions from TX1 to TXj have successfully validated, a (re-)execution of transaction j+1 will pass read-set validation successfully and not require re-execution.

READLAST(k) is implemented in Block-STM via a simple multi-version in-memory data structure that keeps versioned write-sets. A write by TXj is recorded with version j. A read by TXk obtains the value recorded by the latest invocation of TXj with the highest j < k.

A special value ABORTED may be stored at version j when the latest invocation of TXj aborts.

If TXk reads this value, it suspends and resumes when the value becomes set.

VALIDAFTER(j, k) is implemented by scheduling for each TXj a read-set validation of TXk, for every k > j, after TXj completes (re-)executing.

Scheduling

It remains to focus on devising an efficient schedule for parallelizing execution and read-set validations. We present the Block-STM scheduler gradually, starting with a correct but inefficient strawman and gradually improving it in three steps. The full scheduling strategy is described in under 20 lines of pseudo-code.

S-1

At a first cut, consider a strawman scheduler, S-1, that uses a centralized dispatcher that coordinates work by parallel threads.

S-1 Algorithm

// Phase 1:

dispatch all TX’s for execution in parallel ; wait for completion

// Phase 2:

repeat {

dispatch all TX's for read-set validation in parallel ; wait for completion

} until all read-set validations pass

read-set validation of TXj {

re-read TXj read-set

if read-set differs from original read-set of the latest TXj execution

re-execute TXj

}

execution of TXj {

(re-)process TXj, generating a read-set and write-set

}

S-1 operates in two master-coordinated phases. Phase 1 executes all transactions optimistically in parallel. Phase 2 repeatedly validates all transactions optimistically in parallel, re-executing those that fail, until there are no more read-set validation failures.

Recall our running example, a Block B with dependencies TX1 → TX2 → TX3 → {TX4, TX6, TX9}), running with four threads, each transaction taking one time unit (and neglecting all other computation times). A possible execution of S-1 over Block B would proceed along the following time-steps:

1. phase 1 starts. parallel execution of TX1, TX2, TX3, TX4

2. parallel execution of TX5, TX6, TX7, TX8

3. parallel execution of TX9, TX10

4. phase 2 starts. parallel read-set validation of all transactions in which TX2, TX3, TX4, TX6 fail and re-execute

5. continued parallel read-set validation of all transactions in which TX9 fails and re-executes

6. parallel read-set validation of all transactions in which TX3, TX4, TX6 fail and re-execute

7. parallel read-set validation of all transactions in which TX4, TX6, TX9 fail and re-execute

8. parallel read-set validation of all transactions in which all succeed

It is quite easy to see that the S-1 validation loop satisfies VALIDAFTER(j,k) because every transaction is validated after previous executions complete. However, it is quite wasteful in resources, each loop fully executing/validating all transactions.

S-2

The first improvement step, S-2, is to replace both phases with parallel task-stealing by threads. Using insight from S-1, we distinguish between a preliminary execution (corresponding to phase 1) and re-execution (following a validation abort). Stealing is coordinated

via two synchronization counters, one per task type, nextPrelimExecution (initially 1) and nextValidation (initially n+1).

An (re-)execution of TXj guarantees that read-set validation of all higher transactions will be dispatched by decreasing nextValidation back to j+1.

The following strawman scheduler, S-2, utilizes a task stealing regime.

S-2 Algorithm

// per thread main loop:

repeat {

task := "NA"

// if available, steal next read-set validation task

atomic {

if nextValidation < nextPrelimExecution

(task, j) := ("validate", nextValidation)

nextValidation.increment();

}

if task = "validate"

validate TXj

// if available, steal next execution task

else atomic {

if nextPrelimExecution <= n

(task, j) := ("execute", nextPrelimExecution)

nextPrelimExecution.increment();

}

if task = "execute"

execute TXj

validate TXj

} until nextPrelimExecution > n, nextValidation > n, and no task is still running

read-set validation of TXj {

re-read TXj read-set

if read-set differs from original read-set of the latest TXj execution

re-execute TXj

}

execution of TXj {

(re-)process TXj, generating a read-set and write-set

atomic { nextValidation := min(nextValidation, j+1) }

}

Interleaving preliminary executions with validations avoids unnecessary work executing transactions that might follow aborted transactions. To illustrate this, we will once again utilize our running example. The timing of task stealing over our running example is hard to predict because it depends on real-time latency and interleaving of validation and execution tasks. Notwithstanding, below is a possible execution of S-2 over B with four threads that exhibits fewer (re-)executions and lower overall latency than S-1.

With four threads, a possible execution of S-2 over Block B (recall, TX1 → TX2 → TX3 → {TX4, TX6, TX9}) would proceed along the following time-steps:

1. parallel execution of TX1, TX2, TX3, TX4; read-set validation of TX2, TX3, TX4 fail

2. parallel execution of TX2, TX3, TX4, TX5; read-set validation of TX3, TX4 fail

3. parallel execution of TX3, TX4, TX6, TX7; read-set validation of TX4, TX6 fail

4. parallel execution of TX4, TX6, TX8, TX9; all read-set validations succeed

5. parallel execution of TX10; all read-set validations succeed

Importantly, VALIDAFTER(j, k) is preserved because upon (re-)execution of a TXj, it decreases nextValidation to j+1. This guarantees that every k > j will be validated after the j execution.

Preserving READLAST(k) requires care due to concurrent task stealing, since multiple incarnations of the same transaction validation or execution tasks may occur simultaneously. Recall that READLAST(k) requires that a read by a TXk should obtain the value recorded by the latest invocation of a TXj with the highest j < k. This requires to synchronize transaction invocations, such that READLAST(k) returns the highest incarnation value recorded by a transaction. A simple solution is to use per-transaction atomic incarnation synchronizer that prevents stale incarnations from recording values.

S-3

The last improvement step, S-3, consists of two important improvements.

The first is an extremely simple dependency tracking (no graphs or partial orders) that considerably reduces aborts. When a TXj aborts, the write-set of its latest invocation is marked ABORTED. READLAST(k) supports the ABORTED mark guaranteeing that a higher-index TXk reading from a location in this write-set will delay until until a re-execution of TXj overwrites it.

The second one increases re-validation parallelism. When a transaction aborts, rather than waiting for it to complete re-execution, it decreases nextValidation immediately; then, if the re-execution writes to a (new) location which is not marked ABORTED, nextValidation is decreased again when the re-execution completes.

The final scheduling algorithm S-3, has the same main loop body at S-2 with executions

supporting dependency managements via ABORTED tagging, and with early re-validation enabled by decreasing nextValidation upon abort:

S-3 Algorithm

// per thread main loop, same as S-2

...

read-set validation of TXj:

{

re-read TXj read-set

if read-set differs from original read-set of the latest TXj execution

mark the TXj write-set ABORTED

atomic { nextValidation := min(nextValidation, j+1) }

re-execute TXj

}

execution of TXj:

{

(re-)process TXj, generating a read-set and write-set

resume any TX waiting for TXj's ABORTED write-set

if the new TXj write-set contains locations not marked ABORTED

atomic { nextValidation := min(nextValidation, j+1) }

}

S-3 enhances efficiency through simple, on-the-fly dependency management using the ABORTED tag. For our running example of block B,

An execution driven by S-3 with four threads may be able to avoid several of the re-executions incurred in S-2 by waiting on an ABORTED mark.

Despite the high-contention B scenario, a possible execution of S-3 may achieve very close to optimal scheduling as shown below.

A possible execution of S-3 over Block B (recall, TX1 → TX2 → TX3 → {TX4, TX6, TX9})

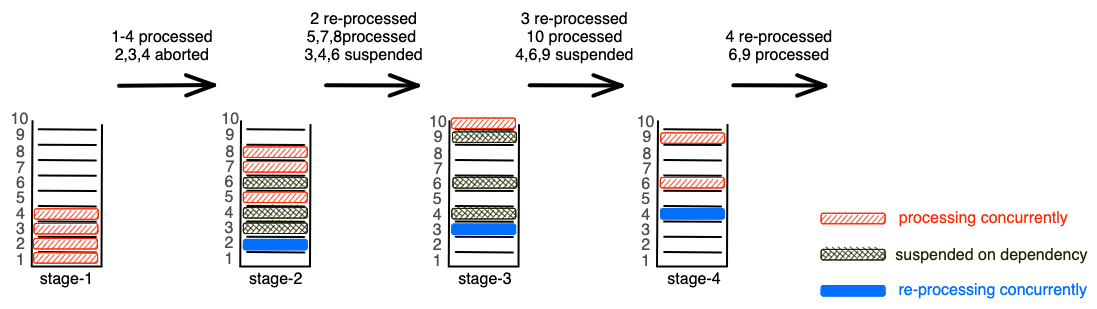

would proceed along the following time-steps (depicted in the figure):

1. parallel execution of TX1, TX2, TX3, TX4; read-set validation of TX2, TX3, TX4 fail; nextValidation set to 3

2. parallel execution of TX2, TX5, TX7, TX8; executions of TX3, TX4, TX6 are suspended on ABORTED; nextValidation set to 6

3. parallel execution of TX3, TX10; executions of TX4, TX6, TX9 are suspended on ABORTED; all read-set validations succeed (for now)

4. parallel execution of TX4, TX6, TX9; all read-set validations succeed

The reason S-3 preserves VALIDAFTER(j, k) is slightly subtle. Suppose that TXj → TXk.

Recall, when TXj fails, S-3 lets (re-)validations of TXk, k > j, proceed before TXj completes re-execution. There are two possible cases. If a TXk-validation reads an ABORTED value of TXj, it will wait for TXj to complete; and if it reads a value which is not marked ABORTED and the TXj re-execution overwrites it, then TXk will be forced to revalidate again.

Conclusion

Through a careful combination of simple, known techniques and applying them to a pre-ordered block of transactions that commit at bulk, Block-STM enables effective speedup of smart contract parallel processing. Simplicity is a virtue of Block-STM, not a failing, enabling a robust and stable implementation. Block-STM has been integrated within the Diem blockchain core (https://github.com/diem/) and evaluated on synthetic transaction workloads, yielding over 17x speedup on 32 cores under low/modest contention.

Disclaimer: The description above reflects more-or-less faithfully the Block-STM approach; for details, see the paper. Also, note the description here uses different names from the paper, e.g.,

ABORTEDreplaces “ESTIMATE”,nextPrelimExecutionreplaces “execution_idx”,nextValidationreplaces “validation_idx”.

Acknowledgement: Many thanks to Zhuolun(Daniel) Xiang for pointing out subtle details that helped improve this post.