September 20th, 2022: see an updated revision titled “BFT on a DAG”.

I found a really simple way to explain how to embed Consensus inside a DAG (Direct Acyclic Graph), which at the same time, is highly efficient.

Synopsis

Emerging Proof-of-Stake blockchains achieve high transaction throughput by spreading transactions reliably as fast as the network can carry them and accumulating them in a DAG. Then, participants interpret their DAG locally without exchanging more messages and determine a total ordering of accumulated transactions.

Given a DAG transport that provides reliable and causally-ordered transaction dissemination, it seems that reaching consensus on total ordering should be really simple. Still, systems built using a DAG, such as Swirlds Hashgraph, Aleph, Narwhal-HS, DAG-Rider, Tusk, and Bullshark, are quite complex. Moreover, protocols in the partial synchrony model like Bullshark actually wait for Consensus steps/timers to add transactions to the DAG.

Here, a simple and efficient DAG-based BFT (Byzantine Fault Tolerant) Consensus embedding – quite possibly the simplest way to build BFT Consensus in a DAG – is described. It operates in a view-by-view manner that guarantees that when the network is stable, only two broadcast latencies are required to reach consensus on all the transactions that have accumulated in the DAG. Importantly, the DAG never has to wait for Consensus steps/timers to add transactions.

This post is meant for pedagogical purposes, not as a full-fledged BFT Consensus system design. The embedding described here stands on the shoulders of previous works, but does not adhere to any one in full, hence it is referred to in this post using a new name Fin. The main takeaway on the evolution of the BFT Consensus field is that by separating reliable transaction dissemination from Consensus, BFT Consensus based on a DAG can be made simple and highly performant at the same time.

Introduction

To scale the BFT (Byzantine Fault Tolerant) Consensus core of blockchains, prevailing wisdom is to separate between two responsibilities.

-

The first is a transport for reliably spreading yet-unconfirmed transactions. It regulates communication and optimizes throughput, but it tracks only causal ordering in the form of a DAG (Direct Acyclic Graph).

-

The second is forming a sequential commit ordering of transactions. It solves BFT Consensus utilizing the DAG.

The advent of building Consensus over a DAG transport is that each message in the DAG spreads useful payloads (transactions). Each time a party sends a message with transactions, it also contributes at no cost to forming a Consensus total ordering of committed transactions. In principle, parties can continue sending messages and the DAG keep growing even when Consensus is stalled, e.g., when a Consensus leader is faulty, and later commit the messages accumulated in the DAG.

It is funny how the community made a full circle, from early distributed consensus systems to where we are today. I earned my PhD more than two decades ago for contributions to scaling reliable distributed systems, guided by and collaborating with pioneers of the field, including Ken Birman, Danny Dolev, Rick Schlichting, Michael Melliar-Smith, Louis Moser, Robbert van Rennesse, Yair Amir, Idit Keidar. Distributed middleware systems of that time, e.g., Isis, Psync, Trans, Total and Transis, were designed for high-throughput by building consensus over causal message ordering (!). An intense debate ensued over the usefulness of CATOCS (Causal and Totally Ordered Communication), leading Cheriton and Skeen to publish a position paper about it, [CATOCS, 1993], followed by Birman’s [response 1 to CATOCS, 1994] and Van Renesse’s [response 2 to CATOCS, 1994].

Recent interest in scaling blockchains appears to settle this dispute in favor of the DAG-based approach: a myriad of leading blockchain projects are being built using DAG-based BFT protocols high-throughput, including Swirlds hashgraph, Blockmania, Aleph, Narwhal & Tusk, DAG-rider, and Bullshark. Still, if you are like me, you might feel that these solutions are a bit complex: there are different layers in the DAG serving different steps in Consensus, and the DAG actually has to wait for Consensus steps/timers to fill layers.

Since the DAG already solves ninety percent of the BFT Consensus problem by supporting reliable, causally ordered broadcast, it seems that we should be able to do simpler/better.

Here, a simple and efficient DAG-based BFT (Byzantine Fault Tolerant) Consensus embedding – referred to as Fin – is described. Fin is quite possibly the simplest way to embed BFT Consensus in a DAG and at the same time, it is highly efficient. It operates in a view-by-view manner that guarantees Consensus progress when the network is stable. In each view, a leader marks a position in the DAG a “proposal”, F+1 out of 3F+1 participants “vote” to confirm the proposal, and everything preceding the proposal becomes committed. Thus, only two broadcast latencies are required to reach consensus on all the transactions that have accumulated in the DAG. Importantly, both proposals and votes completely ignore the DAG structure, they are cast by injecting a single value (a view number) anywhere within the DAG. The DAG transport never waits for view numbers, it embeds in transmissions whatever latest value it was given.

The post is organized as follows:

-

The first section, DAG-T, explains the notion of a reliable, causal broadcast transport that shares a DAG among parties.

-

The second section, Fin, demonstrates the utility of DAG-T through Fin, a BFT Consensus embedded in a DAG which is designed for the partial synchrony model, operates in one-phase, and is completely out of the critical path of DAG transaction spreading. The name Fin, a small part of aquatic creatures like bullshark that controls stirring, stands for the protocol succinctness and its central role in blockchains (and also because the scenarios depicted below look like swarms of fish, and DAG in Hebrew means fish).

-

The third section, DAG-based Solutions, contains comparison notes on DAG-based BFT Consensus solutions.

-

Further reading materials are listed in DAG-based BFT Consensus: Reading list.

DAG-T: A Reliable Causal Broadcast Transport

(If you are already familiar with DAG constructions, you don’t need to read the rest of this section except to note that Consensus is allowed to occasionally invoke setInfo() in order to set a meta-information field piggybacked on future messages.)

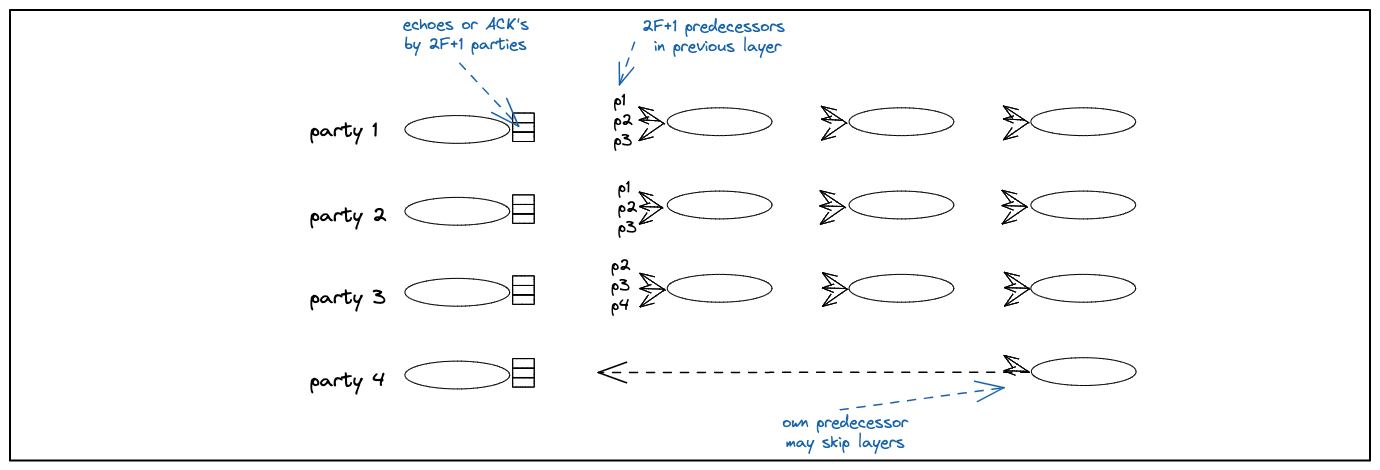

Figure 1:

The construction of a reliable, causal DAG.

Messages carry causal references to preceding messages and a local info value.

Each message is guaranteed to be unequivocal and available through 2F+1 acknowledgements.

DAG-T is a transport substrate for disseminating transactions reliably and in causal order. In a DAG-based broadcast protocol, a party packs meta-information on transactions into a block, adds references to previously delivered messages, and broadcasts a message carrying the block and the causal references to all parties. When another party receives the message, it checks whether it needs to retrieve a copy of any of the transactions in the block and in causally preceding blocks. Once it receives a copy of all transactions in the causal past of a block it can acknowledge it. When 2F+1 acknowledgments are gathered, the message is inserted into the DAG, guaranteeing that DAG messages maintain Reliability, Availability, Integrity, and Causality (defined below). In a nutshell, DAG-T guarantees that all parties deliver the same ordered sequence of messages by each sender and exposes a causal-ordering relationship among them.

The life of transaction dissemination in DAG-T is captured in Figure 1 above:

- Parties collect transactions and send messages that contain blocks of meta-information on transactions and have direct utility.

- Each message carries references to previously delivered messages (see definition of delivered in next step).

These references become the backbone of a causally ordered directed acyclic graph (DAG) structure.

Messages also include a meta-information field

infoset insetInfo(), explained below. - In order for messages to be “delivered”, parties exchange acknowledgements about messages they receive. A message is delivered to a party when it is known that the transactions in the message and all its predecessors have been received and persisted by a quorum of parties, guaranteeing that their availability.

- Parties insert delivered messages into a local DAG that they independently analyse to determine a Consensus total ordering of messages, without sending extra messages.

More specifically, the DAG-T transport substrate exposes two basic API’s, broadcast() and deliver().

broadcast(payload) is an API for a party p to send a message to other parties.

A party’s upcall deliver(m) is triggered when a message m can be delivered.

Each message may refer to preceding messages including the sender’s own preceding message.

Messages are delivered carrying a sender’s payload and additional meta information that can be inspected upon reception.

Every delivered message m carries the following fields:

- m.sender, the sender identity - m.index, a delivery index from the sender - m.payload, contents such as transaction(s) - m.predecessors, references to messages sender has delivered from other parties, including itself. - m.info, a local meta-information field, set in setInfo(), explained below.

DAG-T satisfies the following requirements:

-

Reliability. If a

deliver(m)event happens at an honest party, then eventuallydeliver(m)happens at every other honest party. -

Agreement. If a

deliver(m)happens at an honest party, anddeliver(m')happens at another honest party, such thatm.sender = m'.sender,m.index = m'.indexthenm = m'. -

Validity. If an honest party invokes

broadcast(payload)then adeliver(m)withm.payload = payloadevent eventually happens at all honest parties. -

Integrity. If a

deliver(m)event happens at an honest party, thenpindeed invokedbroadcast(payload)wherem.payload = payload. -

Causality. If a

deliver(m)happens at an honest party, thendeliver(d)events already happened at the party for all messagesdreferenced inm.predecessors. Note that by transitively, this ensures its entire causal history has been delivered.

A Non-Blocking API for Injecting Consensus Protocol Input – setInfo()

To prepare for Consensus decisions, DAG transports usually expose APIs allowing the Consensus protocol to inject input into the DAG.

There is no commonly accepted standard for doing this in the literature. Protocols in the partial synchrony model like Bullshark actually wait for Consensus steps/timers to add transactions to the DAG. Asynchronous protocols like Aleph, Narwhal, DAG-rider, Bullshark, need coin-toss shares from Consensus to fill the DAG.

Here we introduce a minimally-invasive, non-blocking API setInfo(x), that works as follows.

When a party invokes setInfo(x), the DAG-T transport records the value x for its internal use.

Whenever broadcast() is invoked, DAG-T injects the then current value x, which has been last recorded in setInfo(x).

Importantly, DAG-T never waits for setInfo, it embeds in transmissions whatever value it already has.

Implementing DAG-T

There are various ways to implement DAG-T among N=3F+1 parties, at most F of which are presumed Byzantine faulty and the rest are honest.

Echoing. The key mechanism for reliability and non-equivocation is for parties to echo a digest of the first message they receive from a sender with a particular index. When 2F+1 echoes are collected, the message can be delivered. There are two ways to echo, one is all-to-all broadcast over authenticated point-to-point channels a la Bracha Broadcast; the other is converge-cast with cryptographic signatures a la Rampart. In either case, echoing can be streamlined so the amortized per-message communication is linear, which is anyway the minimum necessary to spread the message.

Layering. Transports are often constructed in layer-by-layer regime, as depicted in Figure 2 below. In this regime, each sender is allowed one message per layer, and a message may refer only to messages in the layer preceding it. Layering is done so as to regulate transmissions and saturate network capacity, and has been demonstrated to be highly effective by various projects, including Blockmania, Aleph, and Narwhal.

Layering and Temporary Disconnections. In a layer-by-layer construction, a message includes references to messages in the preceding layer. Sometimes, a party may become temporarily disconnected. When it reconnects back, the DAG might have grown many layers without it. It is undesirable that a reconnecting party would be required to backfill every layer it missed with messages that everyone has to catch up with. Therefore, parties are allowed to refer to their own preceding message across (skipped) layers, as depicted in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2: A temporary disconnect of party 4 and a later reconnect.

Layering and other implementation considerations are orthogonal to the BFT Consensus protocol. As we shall see below, Fin ignores a layer structure of DAG-T, if exists. Here, we only care about the abstract API and properties that DAG-T provides. For further information on DAG implementations, see below further reading.

Fin

Given the strong guarantees of a DAG transport Consensus can be embedded in the DAG quite simply; Fin is quite possibly the simplest DAG-based BFT Consensus solution for the partial synchrony model.

Briefly, Fin works as follows:

-

Views. The protocol operates in a view-by-view manner. Each view is numbered, as in “view(r)”, and has a designated leader known to everyone.

-

Proposing. When a leader enters a new view(r), it sets a “meta-information” field in its coming broadcast to

r. A leader’s message carryingr(for the first time) is interpreted asproposal(r). Implicitly,proposal(r)suggests to commit to the global ordering of transactions all the blocks in the causal history of the proposal. -

Voting. When a party sees a valid leader proposal, it sets a “meta-information” field in its coming broadcast to

r. A party’s message carryingr(for the first time) followingproposal(r)is interpreted asvote(r). -

Committing. Whenever a leader proposal gains F+1 valid votes, the proposal and its causal history become committed.

-

Complaining. If a party gives up waiting for a commit to happen in view(r), it sets a “meta-information” field in its coming broadcast to

-r. A party’s message carrying-r(for the first time) is interpreted ascomplaint(r). Note, a message by a party carryingrthat causally follows acomplaint(r)by the party, if exists, is not interpreted as a vote. -

View change. Whenever a commit occurs in view(r) or 2F+1

complaint(r)are obtained, the next view(r+1) is enabled.

Importantly, proposals, votes, and complaints are injected into the DAG at any time, independent of layers.

Likewise, protocol views do NOT correspond to DAG layers, but rather, view numbers are explicitly embedded in the meta-information field of messages.

View numbers are in fact the only meta information Consensus injects into the DAG (through the asynchronous setInfo() API).

This property is a key tenet of the DAG/Consensus separation, allowing the DAG to continue spreading transactions with Cosensus completely out of the critical path.

In a nutshell, the reason that the simple Fin commit-logic is safe is because there is no need to worry about a leader equivocating, because DAG-T prevents equivocation, and there is no need for a leader to justify its proposal because it is inherently justified through the proposal’s causal history within the DAG. Advancing to the next view is enabled by F+1 votes or 2F+1 complaints. This guarantees that if a proposal becomes committed, the next (justified) leader proposal contains a reference to it.

The full protocol is decribed in pseudo-code below in Fin Pseudo-Code. A step by step scenarios walkthrough is provided next.

Scenario-by-scenario Walkthrough

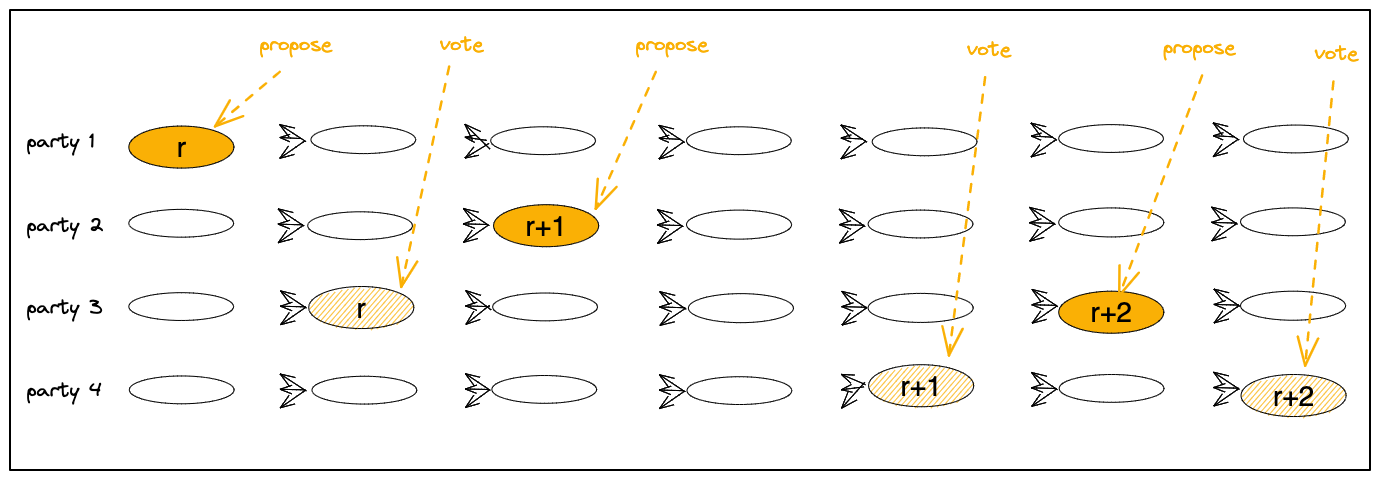

Happy path scenario.

Each view(r) has a pre-designated leader, denoted leader(r), which is known to everyone.

leader(r) proposes in view(r) by setting its meta-information value to r via setInfo(r).

Thereafter, transmissions by the leader will carry the new view number.

The first view(r) message by the leader is interpreted as proposal(r).

The proposal implicitly extends the sequence of transactions with the transitive causal predecessors of proposal(r).

In Figure 3 below,

leader(r) is party 1 and its first message in view(r) is denoted with a full yellow oval,

indicating it is proposal(r).

When a party receives proposal(r), it advances the meta-information value to r via setInfo(r).

Thereafter, transmissions by the party will carry the new view number and the first of them be interpreted as vote(r) for proposal(r).

A proposal that has a quorum of F+1 votes is considered committed.

In Figure 3 below,

party 3 votes for proposal(r) by advancing its view to r, denoted with a striped yellow oval. proposal(r) now has the required quorum of F+1 votes (including the leader’s implicit vote), and it becomes committed.

When a party sees F+1 votes in view(r) it enters view(r+1).

An important feature of Fin is that votes may arrive without slowing down progress.

The DAG meanwhile fills with useful messages that may become committed at the next view.

This feature is demonstrated in the scenario below at view(r+1).

The view has party 2 as leader(r+1) proposing proposal(r+1), but

vote(r+1) messages do not arrive at the layer immediately following the proposal, only later.

No worries! Until proposal(r+1) has the necessary quorum of F+1 of votes and becomes committed,

the DAG keeps filling with messages that may become committed at the next view, e.g., view(r+2).

Figure 3:

Proposals, votes, and commits in view(r), view(r+1), view(r+2).

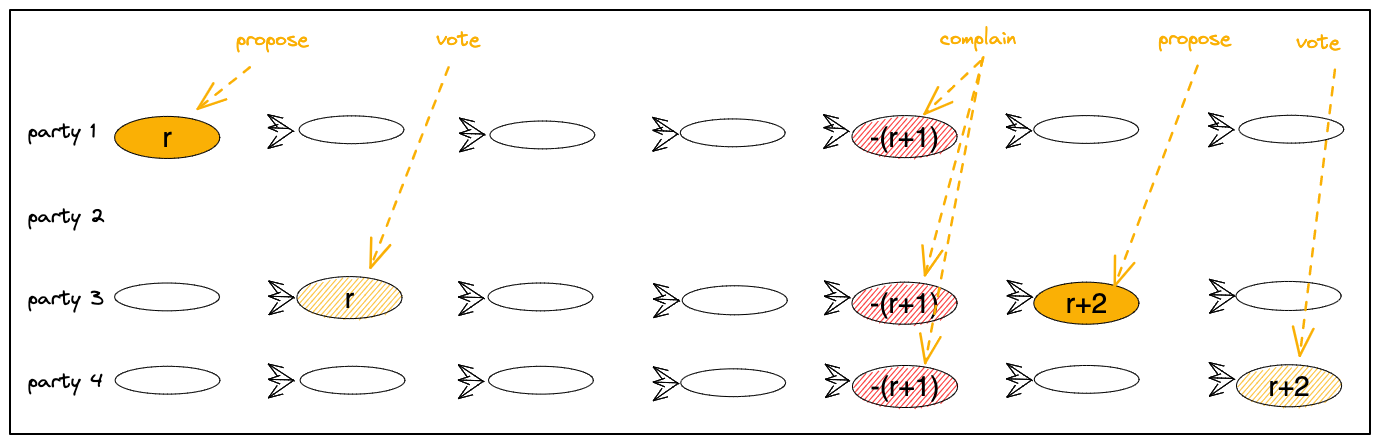

Scenario with a faulty leader.

If the leader of a view is faulty or disconnected, parties will eventually time out and set their meta-information to minus the view-number, e.g., -(r+1) for a failure of view(r+1) .

Their next broadcasts are interpreted as complaining that there is no progress in view(r+1).

When a party sees 2F+1 complaints about view(r+1), it enters view(r+2).

In Figure 4 below, the first view view(r) proceeds normally.

However, no message marked view(r+1) by party 2 who is leader(r+1) arrives, showing as a missing ovals.

No worries! As depicted, DAG transmissions continue filling layers, unaffected by the leader failure.

Hence, faulty views have utility in spreading transactions.

Eventually, parties 1, 3, 4 complain about vire(r+1) by setting their meta-information to -(r+1), showing as striped red ovals.

After 2F+1 complaints are collected, the leader of view(r+2) posts a messages that has meta-information set to r+2, taken as proposal(r+2).

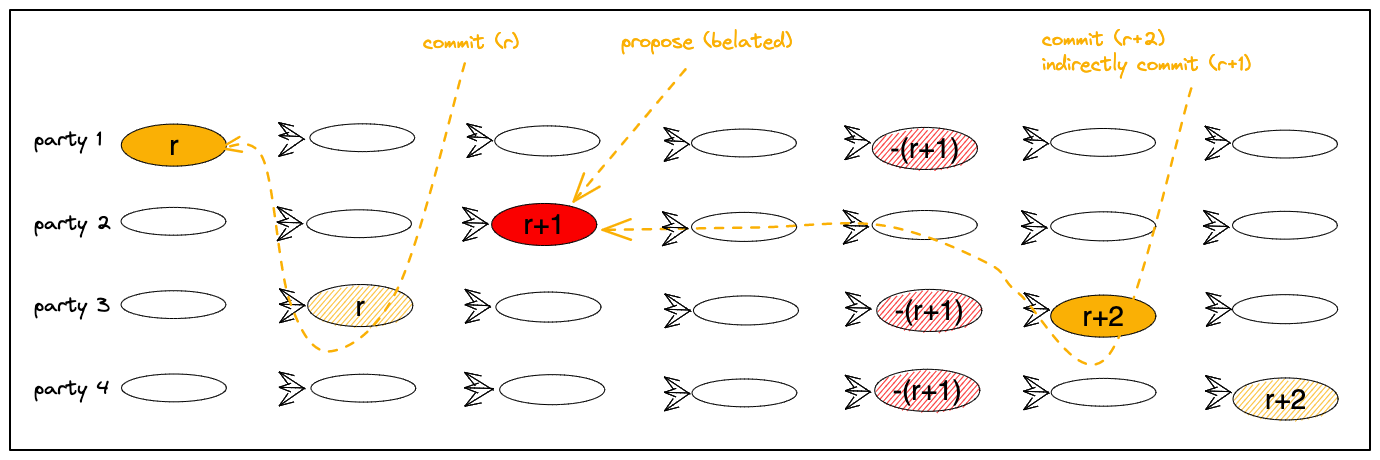

Figure 4:

A faulty view(r+1) and recovery in view(r+2).

Scenario with a slow leader.

A slightly more complex scenario is depicted in Figure 5 below.

Here, leader(r+1) emits proposal(r+1) that is too slow to arrive and parties 1, 3 and 4, complain about a view failure.

This enables view(r+2) to start and progress to commit proposal(r+2). When proposal(r+2) commits,

in this scenario it causally follows proposal(r+1) hence it indirectly commits it.

Figure 5:

A belated proposal in view(r+1) being indirectly committed in view(r+2).

Fin in Pseudo-code

Each message in the DAG is interpreted as follows:

*. A message m that carries m.info = r is referred to as a view(r) message.

*. The first view(r)-message from the leader of view(r) is referred to as proposal(r)

*. The first view(r)-message from a party is referred to as vote(r) (note, proposal(r) by the leader is also its vote(r))

*. A message m that carries m.info = -r is referred to as complaint(r)

*. A proposal(r) is "justified" if proposal(r).predecessors refers to either F+1 justified vote(r-1) messages or 2F+1 complaint(r-1) messages (or r=1)

*. A vote(r) is "justified" if proposal(r).predecessors refers to a justified proposal(r) and does not refer to complaint(r) by the same sender

Party p performs the following operations for view(r):

1. Entering a view.

Upon entering view(r), party p starts a view timer set to expire after a pre-determined view delay.

2. Proposing.

The leader leader(r) of view(r) waits to deliver F+1 vote(r-1) messages or 2F+1 complaint(r-1) messages, and then invokes setInfo(r).

Thereafter, the next transmission by the leader will carry the new view number, hence become proposal(r) (as well as its vote(r)).

3. Voting.

Each party p other than the leader waits to deliver proposal(r) from leader(r) and then invokes setInfo(r).

Thereafter, the next transmission by p will carry the new view number, hence become vote(r) for the leader's proposal.

4. Committing.

A justified proposal(r) becomes committed if F+1 justified vote(r) messages are delivered.

Upon a commit of proposal(r), a party disarms the view(r) timer.

4.1. Ordering commits.

If proposal(r) commits, messages are appended to the committed sequence as follows.

First, among proposal(r)'s causal predecessors, the highest justified proposal(r') is (recursively) ordered.

After it, remaining causal predecessors of proposal(r) which have not yet been ordered are appended to the committed sequence

(within this batch, ordering can be done using any deterministic rule to linearize the partial ordering into a total ordering.)

5. Expiring the view timer.

If the view(r) timer expires, a party invokes setInfo(-r).

Thereafter, the next transmission by p will carry the negative view number, hence become complaint(r), an indication of expiration of r.

6. Advancing to next view.

A party enters view(r+1) if the DAG satisfies one of the following two conditions:

(i) A commit of proposal(r) happens.

(ii) 2F+1 complaint(r) messages are delivered.

Fin Analysis

Fin is minimally integrated into DAG-T, simply setting the meta-information field occasionally. Importantly, at no time is transaction broadcast slowed down by the Fin protocol. Consensus logic is embedded into the DAG structure simply by injecting view numbers into it. Importantly, the DAG transport never waits for view numbers, it embeds in transmissions whatever value it already has.

The reliability and causality properties of DAG-T makes arguing about correctness very easy, though a formal proof of correctness is beyond the scope of this post.

- Safety.

Briefly, the safety of commits is as follows. If ever

proposal(r)becomes committed, then it is in the causal past of F+1 parties that voted for it. A justified proposal of any higher view must refer (directly or indirectly) to F+1vote(r)messages, or to 2F+1 justifiedcomplaint(r)messages of which one follows aproposal(r). In either case, a commit in such a future view causally follows a vote forproposal(r), hence, it (re-)commits it.

Conversely, when proposal(r) commits, it may cause a proposal in a lower view, proposal(r'), where r' < r, to become committed for the first time.

Safety holds because future commits will order proposal(r) and its causal past recursively.

-

Liveness. The protocol liveness during periods of synchrony stems from two key mechanisms.

First, after GST (Global Stabilization Time), i.e., after communication has become synchronous, views are inherently synchronized through DAG-T. For let \(\Delta\) be an upper bound on communication after GST. Once a

view(r)with an honest leader is entered by the first honest party, within \(2 * \Delta\), all the messages seen by partypare delivered by both the leader and all other honest parties. Hence, within \(2 * \Delta\), all honest parties enterview(r)as well. Within \(4 * \Delta\), theview(r)proposal and votes from all honest parties are spread to everyone.Second, so long as view timers are set to be at least \(4 * \Delta\), a future view does not preempt a current view’s commit. For in order to start a future view, its leader must collect either F+1

vote(r)messages, hence commitproposal(r); or 2F+1complaint(r)expiration messages, which is impossible as argued above.

We now remark about Fin’s communication complexity. Protocols for the partial synchrony model have unbounded worst case by nature, hence, we concentrate on the costs incurred during steady state when a leader is honest and communication with it is synchronous:

-

DAG message cost: In order for DAG messages to be delivered reliably, it must implement reliable broadcast. This incurs either a quadratic number of messages carried over authenticated channels, or a quadratic number of signature verifications, per broadcast. In either case, the quadratic cost may be amortized by pipelining, driving it is practice to (almost) linear per message.

-

Commit message cost: Fin sends 3F+1 broadcast messages, a proposal and votes, per decision. A decision commits the causal history of the proposal, consisting of (at least) a linear number of messages. Moreover, each message may carry multiple transaction in its payload. As a result, in practice the commit cost is amortized over many transactions.

-

Commit latency: The commit latency in terms of DAG messages is 2, one proposal followed by votes.

DAG-based Solutions

Narwhal is a DAG transport after which DAG-T is modeled. It has a layer-by-layer structure, each layer having at most one message per sender and referring to 2F+1 messages in the preceding layer. A similarly layered DAG construction appears earlier in Aleph.

Narwhal-HS is a BFT Consensus protocol based on HotStuff for the partial synchrony model, in which Narwhal is used as a “mempool”. In order to drive Consensus decisions, Narwhal-HS adds messages outside Narwhal, using the DAG only for spreading transactions.

DAG-Rider and Tusk build randomized BFT Consensus for the asynchronous model “riding” on Narwhal, These protocols are “zero message overhead” over the DAG, not exchanging any messages outside the Narwhal protocol. DAG-Rider (Tusk) is structured with purpose-built DAG layers grouped into “waves” of 4 (2) layers each. Narwal waits for the Consensus protocol to inject input value every wave, though in practice, this does not delay the DAG materially.

Bullshark builds BFT Consensus riding on Narwhal for the partial synchrony model. It is designed with 8-layer waves driving commit, each layer purpose-built to serve a different step in the protocol. Bullshark is a “zero message overhead” protocol over the DAG, however, due to a rigid wave-by-wave structure, the DAG is modified to wait for Bullshark timers/steps to insert transactions into the DAG. In particular, if leader(s) of a wave are faulty or slow, some DAG layers wait to fill until consensus timers expire:

“We, in contrast, optimize for the common case conditions and thus have to make sure that parties do not advance rounds too fast.”, “To make sure all honest parties get a chance to vote for steady state leaders, an up-to-date honest party

pwill try to advance(viatry_advance_round) to the second and forth rounds of a wave only if (1) the timeout for this round expired or (2)pdelivered a vertex from the wave predefined first and second steady-state leader, respectively.” Bullshark 2022

Fin builds BFT Consensus riding on DAG-T for the partial synchrony model with “zero message overhead”.

Uniquely, it incurs no transmission delaying whatsoever.

To achieve Consensus over DAG-T, Fin requires only injecting values into transmissions in a non-blocking manner via setInfo(v).

Once a setInfo(v) invocation completes, future emissions by the DAG-T carry the value v in the latest setInfo(v) invocation.

The value v is opaque to the DAG-T and is of interest only to the Consensus protocol.

In terms of protocol design, all of the above solutions are relatively succinct, but arguably, Fin is the simplest. DAG-Rider, Tusk and Bullshark are multi-stage protocols embedded into DAG multi-layer “waves” (4 layers in DAG-Rider, 2-3 in Tusk, 8 in Bullshark). Each layer is purpose-built for a different step in the Consensus protocol, with a potential commit happening at the last layer. Fin is single-phase, and view numbers can be injected into the DAG at any time, independent of the layer structure.

| Protocol | Model | External messages used | DAG must be layered | DAG broadcasts wait for Consensus | Min commit latency* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total, 1991 | asynchronous | none | no | no | eventual |

| Swirlds Hashgraph, 2016 | asynchronous | none | no | no | eventual |

| Aleph, 2019 | asynchronous | none | yes | yes (coin-tosses) | expected constant |

| Narwhal-HS, 2021 | partial-synchrony | yes | yes | no | 6 |

| DAG-Rider, 2021 | asynchronous | none | yes | yes (coin-tosses) | 4 |

| Tusk, 2021 | asynchronous | none | yes | yes (coin-tosses) | 3 |

| Bullshark, 2022 | partial-synchrony (with asynch fallback) | none | yes | yes (timers) | 2 |

| Fin, 2022 | partial-synchrony | none | no | no | 2 |

* asynchronous commit latency is measured as length of causal message chain

There is no question that software modularity is advantageous, since it removes the Consensus protocol from the critical path of communication. That said, most solutions do not rely on a DAG transport in a pure black-box manner. As discussed above, randomized Consensus protocols, e.g., DAG-rider and Tusk, inject into the DAG randomized coin-tosses from the Consensus protocol. Protocols for the partial synchrony model, e.g., Bullshark, modify the DAG to wait for Consensus protocol round timers, in order to ensure progress during periods of synchrony.

In other words, rarely is the case that all you need is DAG.

In a pure-DAG solution, no extra messages are exchanged by the Consensus protocol nor is it given an opportunity to inject information into the DAG or control message emission. Parties passively analyze the DAG structure and autonomously arrive at commit ordering decisions, even though the DAG is delivered to parties incrementally and in potentially different order.

Total and ToTo are pre- blockchain era, pure-DAG total ordering protocols for the asynchronous model. Swirlds Hashgraph is the only blockchain era, pure-DAG solution to our knowledge. It makes use of bits within messages as pseudo-random coin-tosses in order to drive randomized Consensus. All of the above pure DAG protocols are designed without regulating DAG layers, and without injecting external common coin-tosses to cope with asynchrony. As a result, they are both quite complex and their convergence slow.

Fin finds a sweet-spot: albeit not being a pure-DAG protocol, it is a simple and fast DAG-based protocol, that injects values into the DAG in a non-intrusive manner.

Acknowledgement: Many thanks to Lefteris Kokoris-Kogias for pointing out practical details about Narwhal and Bullshark, that helped improve this post.

DAG-based BFT Consensus: Reading list

Pre-blockchains era:

-

“Exploiting Virtual Synchrony in Distributed Systems”, Birman and Joseph, 1987. [Isis]

-

“Asynchronous Byzantine Agreement Protocols”, Bracha, 1987. [Bracha Broadcast]

-

“Preserving and Using Context Information in Interprocess Communication”, Peterson, Buchholz and Schlichting, 1989. [Psync]

-

“Broadcast Protocols for Distributed Systems”, Melliar-Smith, Moser and Agrawala, 1990. [Trans and Total]

-

“Total Ordering Algorithms”, Moser, Melliar-Smith and Agrawala, 1991. [Total (short version)]

-

“Byzantine-resilient Total Ordering Algorithms”, Moser and Melliar Smith, 1999. [Total]

-

“Transis: A Communication System for High Availability”, Amir, Dolev, Kramer, Malkhi, 1992. [Transis]

-

“Early Delivery Totally Ordered Multicast in Asynchronous Environments”, Dolev, Kramer and Malki, 1993. [ToTo]

-

“Understanding the Limitations of Causally and Totally Ordered Communication”, Cheriton and Skeen, 1993. [CATOCS]

-

“Why Bother with CATOCS?”, Van Renesse, 1994. [Response 1 to CATOCS]

-

“A Response to Cheriton and Skeen’s Criticism of Causal and Totally Ordered Communication”, Birman, 1994. [Response 2 to CATOCS]

-

“Secure Agreement Protocols: Reliable and Atomic Group Multicast in Rampart”, Reiter, 1994. [Rampart].

Blockchain era:

-

“The Swirlds Hashgraph Consensus Algorithm: Fair, Fast, Byzantine Fault Tolerance”, Baird, 2016. [Swirlds Hashgraph]

-

“Blockmania: from Block DAGs to Consensus”, Danezis and Hrycyszyn, 2018. [Blockmania].

-

“Aleph: Efficient Atomic Broadcast in Asynchronous Networks with Byzantine Nodes”, Gągol, Leśniak, Straszak, and Świętek, 2019. [Aleph]

-

“Narwhal and Tusk: A DAG-based Mempool and Efficient BFT Consensus”, Danezis, Kokoris-Kogias, Sonnino, and Spiegelman, 2021. [Narwhal and Tusk]

-

“All You Need is DAG”, Keidar, Kokoris-Kogias, Naor, and Spiegelman, 2021. [DAG-rider]

-

“Bullshark: DAG BFT Protocols Made Practical”, Spiegelman, Giridharan, Sonnino, and Kokoris-Kogias, 2022. [Bullshark]