The BFT lens: HotStuff and Casper

Today I am going to overview a new algorithmic foundation called ‘HotStuff the Linear, Optimal-Resilience, One-Message BFT Devil’ (in short, HotStuff), developed jointly with my colleagues Ittai Abraham and Guy Gueta, and harness it to explain the safety and liveness of Casper the Friendly Finality Gadget.

The key take-aways are:

- We have excellent foundations for Byzantine fault tolerance (or BFT), yet incredible innovation is actually happening in the arena.

- At first glance, BFT protocols in the age of blockchains, e.g., Tendermint, Casper the Friendly GHOST, and Casper the Friendly Finality Gadget, have very different “feel” from classical solutions like DLS, PBFT and others. In particular, a new proposer in these protocols makes a proposition without carrying an explicit proof of safety. This is the main source of complexity in traditional BFT solutions, and evidently intimidates folks outside the community. However, we have recently been able to articulate a unified foundation called HotStuff, that captures both worlds.

- HotStuff can be utilized to reason about Casper, give a simple argument for its safety, and express rigorous conditions for liveness.

- The HotStuff contains a pluggable `beacon’ abstraction, a mechanism and policy for triggering proposals. In particular, we describe an implementation which uses a rotating-proposer that achieves superior communication complexity than previously known BFT solutions.

In a future post, I will discuss the interplay between finality gadgets and the security of the PoW chain they finalize.

Blockchain and BFT

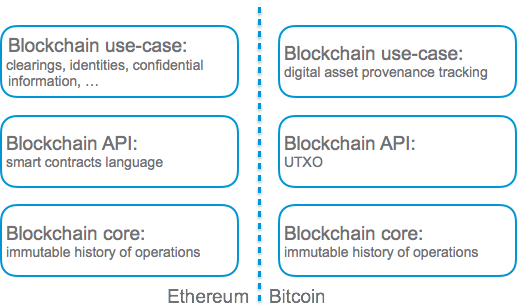

A blockchain is a state-machine-replication (SMR) engine that has a 3-layer architecture. The foundation is a consensus core that forms agreement over an immutable sequence of updates to a shared state. This is known as the Byzantine fault tolerance problem, or BFT. The consensus algorithm in Bitcoin, Nakamoto Consensus, solves BFT for permissionless settings, with an unknown universe of participants whose behavior is untrusted.

On top of BFT is a layer that specifies a state-machine API for updates. Bitcoin’s state-machine and state-updates use a limited scripting language; Ethereum expands the state-machine and state-updates with a Turing complete abstraction (whose resources are bounded).

The top layer represents the application which in Bitcoin is the shared provenance tracking of digital assets, and in Ethereum, could be anything decentralized.

The BFT Problem Model

The classical settings for BFT solutions is a permissioned set of n=3f+1 replicas, of which a threshold of 2f+1 is presumed to behave according to spec and not fail. These are called correct replicas. The other f replicas are called Byzantine. The permissioned model is quite different from the settings in which Bitcoin blockchain is set to solve the Consensus problem, where participants are unknown, and they are admitted without explicit permission (hence they are called permissionless). Participation is instead conditioned on Proof-of-Work (PoW). From a foundational point of view the two models are quite close, both solve consensus with a resilience threshold, the permissioned model on the number of Byzantine replicas, the PoW model on the cumulative compute power of Byzantine miners. Another variant is the Proof-of-Stake (PoS) model that puts a resilience threshold on the cumulative stake of Byzantine stake holders.

A key element of the BFT problem definition is a partial synchrony model concerning communication delays. This assumption is worthy of attention:

- A synchronous model assumes a known upper bound on transmission delays. In practice, for this assumption to hold in a large-scale decentralized system, the bound needs to be very high. Waiting for this bound on each step provides a worst-case upper bound, but it also determines a (pessimistic) lower-bound.

- On the other hand, if there is no known bound on transmission delays, then it is theoretically possible that an algorithm will keep running into adversarial scheduling that will prevent it from ever converging (see the celebrated FLP impossibility result).

In 1988, a beautiful solution approach was given in DLS that strikes a practical path between these two extremes. DLS guarantees that safety is never compromised, even during periods of asynchrony. Progress is guaranteed during periods of synchrony. This solution approach is extremely robust. First, it allows progress at the network speed, not in a lock-step pessimistic manner. Second, it allows to set very conservative synchronous bounds, which makes partial synchrony assumption realistic.

Safety despite asynchrony is another key aspect in which solutions for the permissioned BFT model differ from solutions in the permissionless one. The PoW model is inherently synchronous, hence may lose safety under asynchrony attacks. For the same reason, as alluded to above, solutions in the synchronous settings such as Nakamoto Consensus inherently suffer from high latency.

Revisiting BFT

There are various reasons to revisit BFT:

Permissionless blockchains.

Within permissionless settings, people are looking for ways to harness BFT to alleviate various deficiencies of Nakamoto Consensus. Several ‘hybrid’ schemes were developed that combine PoW chains with BFT to increase throughput, decrease latency to finality, and promote fairness. Byzcoin, Bitcoin-NG, and Hybrid Consensus use a permissionless chain to determine a participant/proposer rotation in a reconfigurable BFT engine. Solida/Solidus is a is a chainless BFT protocol in the permissionless settings that uses PoW to generate propositions and rotate members. Thunderella is a BFT engine that uses a permissionless chain for recovery from failures. Casper the Friendly Finality Gadget and Casper the Friendly GHOST use a BFT engine as a finalizing authority over a permissionless chain.

Permissioned blockchains.

People have rekindled interest in traditional BFT solutions for permissioned/“consortium” settings. They revisit the classical foundations, e.g., PBFT and BFT-SMaRt, as well as invent new permissioned solutions targeting performance, fairness and privacy issues, e.g., Tendermint, Honey Badger, and Algorand.

From PBFT via HotStuff to Casper

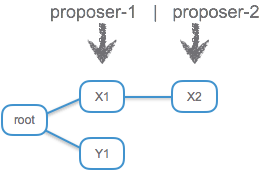

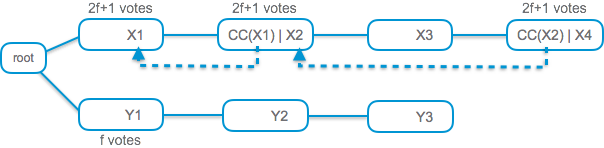

The BFT literature explicitly talks about rounds and message; instead, we will look at a chain of propositions made level by level, as depicted here:

The figure above shows that at each level of the chain, there may be one or more propositions. Because we are in a Byzantine model, conflicting propositions represent either the case of a faulty proposer that equivocates, or the case where there are concurrently contending proposers. From a safety point of view, there really is no difference between these cases, the algorithm must maintain safety against conflicting propositions. Having (eventually) an uncontested leader (or proposition) is required only for liveness.

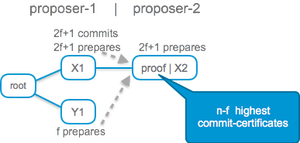

In PBFT, at each level, a proposer tries to get a unique value ‘locked’ in two phases, ‘prepare’ and ‘commit’. First, a proposer tries to obtain 2f+1 prepares. A set of 2f+1 signed prepares is called a ‘commit-certificate’. In the second phase, replicas commit to the commit-certificate. If 2f+1 replicas commit to a certificate, it becomes a committed decision.

At the next level, the proposer for the level tries to reach a decision as well. The proposer needs to choose one branch to extend. For example, in the scenario depicted above, if a decision on X1 was reached at level 1, then the level-2 proposer must choose to extend the ‘X’ branch.

In PBFT, a new proposer collects commit-certificates from 2f+1 replicas. The highest commit-certificate in the set is a safe branch to extend. The proposer sends the set of 2f+1 commit-certificates as proof of safety along with a new proposition. A replica accepts a proposition from a new proposer only if it carries such a proof.

In our example, because 2f+1 replicas have committed to X1, the quorum at level 2 will intersect the quorum that committed to X1 in at least one correct replica. Therefore, the second proposer must choose branch ‘X’.

The PBFT quadratic (all-all) exchange of commit votes with signatures has somewhat bad reputation as being costly and impractical, compared with linear solutions for benign SMR, e.g., Paxos and Raft. Additionally, a new proposer proof incurs a communication cost of O(n3) per proposer-replacement. Even if the system is synchronous, a cascade of f failures may cause f proposer replacements and a quartic communication cost, O(n4).

For completeness, let me briefly mention two classes of improvements that were suggested over PBFT. The first was introduced by the PBFT authors in the PBFT, ACM TOCS version. It replaces signatures on messages with vectors carrying two-way authenticators. There are pros and cons: two-way authenticators are much faster to compute and verify, but complicat the protocol, and increase communication complexity by a factor n. The second one is a line of works that introduce an optimistically fast track to decision. This may be trickier than it seems. We recently surfaced in an ArXiv note on Revisiting Fast PBFT safety and liveness issues in state-of-art solutions. We built a system called SBFT that implements fast decision track correctly. SBFT substantially improves on PBFT performance and scaling. In an accompanying ArXiv note, we provide foundational guidelines on the Thelma, Velma, and Zelma optimistically fast BFT protocols. All of these improvements optimize for good conditions, but their proposer replacement protocol remains the same as PBFT.

HotStuff

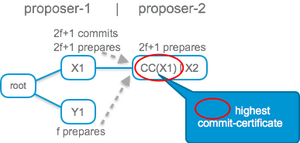

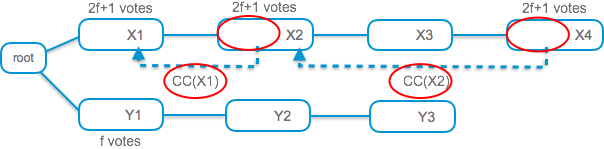

HotStuff reduces by factor n the PBFT proposer proof. This does not make the protocol more complex, on the contrary, it considerably simplifies it. In HotStuff, a new proposer carries only one commit-certificate, the highest-level certificate it knows. Replicas reject a proposition if it conflicts with the highest-level certificate they committed to. This modification is very simple, but as I said, suprisingly powerful. It is illustrated below, PBFT on the left, the HotStuff linear proposer protocol on the right:

An ArXiv manuscript on HotStuff describes how to drive down the communication by another factor n by employing threshold cryptography.

The next modification will make the HotStuff protocol look much more like a blockchain than a BFT protocol. Again, this is a small but powerful modification. In HotStuff, the commit-phase of each level is pushed into the prepare-phase of the next level. We will refer to the single per-level locking phase as ‘vote’. This works as follows.

When a proposer extends the chain with a new value, it optionally includes in the proposition the commit-certificate for the previous level. A vote on the proposition is both an explicit prepare and an implicit commit. It is an explicit prepare on the new value. And if the proposition includes a commit-certificate for the preceding level, it is an implicit commit on the certificate. The complete HotStuff framework is depicted below.

It is safe for proposers not to include in a proposition a commit-certificate for the preceding level. But note that a decision may be reached only at levels in which a proposer does include a commit-certificate for the preceding level. The same happens in PBFT: A commit-phase may either complete, or a timeout is reached and a proposer transitions to the next level without a decision.

The HotStuff “Pseudo-code”

The entire HotStuff protocol is a one-message exchange. The HotStuff framework explicitly separates an abstract mechanism for progress, called a ‘beacon’, allowing for different pluggable implementations:

Beacon functionality:

propose: ( level, commit-certificate, new command )

Infinitely often, the beacon must broadcast for two consecutive levels unique propositions that do not conflict with the highest-level existing commit-certificate.

Replica functionality:

vote: ( level, commit-certificate, new command )

The replica functionality is the same as before, simply merging the prepare for one level with the (optional) commit of the preceding level. As before, replicas reject a proposition if it conflicts with the highest-level commit-certificate they hold.

The full details are described in an ArXiv manuscript on HotStuff. The full manuscript elaborates on several possible materializations of the beacon functionality: Hardware clocks, proposer rotation, and PoW.

Casper

We first regard Casper as a pure BFT engine, but hint to its intended use-case by referring to participants as ‘validators’ instead of replicas. Having introduced HotStuff, we can describe the Casper BFT protocol in a single-step refinement. The gist of it is quite simple. Casper moves the responsibility for pushing a commit-certificate from the beacon-functionality to peer-to-peer dissemination among the validators.

More specifically, each validator signs its vote and sends it directly to a random subset of the validators. Validators forward votes they receive at random for a while. This gossip-style spreading strategy guarantees with high probability that all validators will collect a commit-certificate within a reasonable time frame.

Once a replica obtains a commit-certificate, it refers to it in its vote at the next level. The figure below depicts Casper and highlights the differences from HotStuff:

Removing the responsibility from the proposer role to collect and distribute commit-certificates is inherent for the setting that Casper addresses, as discussed below.

This variation is safe, replicas can indeed spread votes among themselves. It is live, but just like HotStuff and PBFT, progress depends on certain synchrony. In HotStuff, proposers (occasionally) need to collect a commit-certificate from the preceding level in order to make progress. In Casper, proposers do not collect, nor spread, commit-certificates. Instead, proposers must (occasionally) wait sufficiently long for the validators to spread votes among themselves and obtain commit-certificates in order to make progress. This requires proposers to (occasionally) delay for the worst case dissemination bound. Recall what I said above: Relying on synchrony provides a worst-case upper bound, but sets a (pessimistic) lower-bound.

As mentioned above, the complete HotStuff solution achieves factor n improvement in communication complexity by applying threshold cryptography. This improvement relies on a proposer’s active involvement.

The Casper Finality Engine

The motivation for a finality engine is given by Buterin in an article titled Minimal Slashing Conditions. In a PoW chain, there is no explicit decision on blocks. As a block becomes buried deeper in the chain, it becomes harder to fork the chain below the block’s depth. Hence, the degree of ‘finality’ of a block is proportional to its depth. The idea of a finality engine is to provide an accompanying decision by a BFT engine on blocks at arbitrary depths. The guarantee provided by the BFT engine is indepedent of the depth of the block.

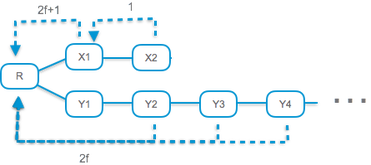

Technically, the interplay between Casper and the PoW chain works as follows. Casper is a BFT mechanism designed to work with a PoW as a ‘beacon’. The public PoW chain serves propositions to the BFT engine, and the engine forms agreement on a single chain. In order for this to work, the finality engine does not need to impose any change of format or content on the public chain. This is already illustrated above, simply replacing internal proposers with an auxiliary source. As explained above, this materialization of the ‘beacon’ functionality is safe.

In order to provide progress, the PoW chain generating propositions for the BFT engine must fulfill the beacon liveness conditions. Casper stipulates that the PoW chain maintains the following three conditions that together guarantee beacon liveness:

-

- First, propositions need to extend a branch from the highest-level committed block, because decisions by the finality engine are irreversible.

- Second, the source generating the propositions must (occasionally) allow time for the validators to disseminate votes and collect commit-certificates in between propositions.

A commit-certificate is formed on the (short) ‘X’ branch. One correct validator is “trapped” by voting on this commit-certificate. In this case, the Casper commandments prohibit this validator from ever participating in votes on the ‘Y’ branch. The PoW chain must therefore extend the ‘X’ branch, or else, Casper may get stuck.

- Last, it is not enough to take the longest chain from the last committed, as might be natural to expect. The PoW chain must extend a branch that contains the commit-certificate with the highest level. (See illustration of this condition on the right.)

Under the above three conditions, Casper provides liveness.

Epilogue

When we began our exploration of new-wave BFT protocols like Tendermint and Casper, they appeared quite different from traditional BFT protocols like DLS and PBFT. I hope that HotStuff provided a useful algorithmic framework to discuss both worlds.

Acknowledgements

Most of the material discussed here was developed jointly with Ittai Abraham.

In addition, many thanks to Ittai, Bryan Fink and Linas Tumasonis

for helpful comments with this blogpost.