The BFT lens: Tendermint

This is the second post discussing:

Today I am going to overview the Tendermint core, a BFT algorithm described in several white-papers [tendermint wiki, Buchman’s thesis 2016, Kwon’s manuscript 2014].

Tendermint was the first in a series of “permissioned” blockchain BFT solutions based off PBFT, followed by Casper and HotStuff. The algorithm below borrows from the three (non-identical) Tendermint descriptions above as best I could; I refer to the variant described here as TDRMNT.

In a nutshell:

- TDRMNT has a straight-forward safety argument, and provides liveness under synchrony conditions articulated below.

- Using a unified framework for PBFT, TDRMNT, Casper and HotStuff reveals interesting algorithmic complexity tradeoffs of the four solutions: Drastic simplicity of proposer-replacement in TDRMNT compared with PBFT; enhanced concurrency improvement in Casper compared with TDRMNT; and reduced communication complexity of HotStuff compared with all previous solutions.

In a future post, I will discuss issues around behavior accountability in blockchain BFT solutions, and the interplay between security and accountability.

TDRMNT

Model

TDRMNT is a BFT engine that forms a chain of consensus decisions in the classical, “permissioned” BFT settings: Safety is guaranteed in a group of n=3f+1 replicas (they are called validators in Tendermint) containing up to f byzantine faults. Progress is maintained during periods of synchrony. Two seminal results in the same model are DLS, demonstrating solvability, and PBFT, a practical solution that optimizes for the case of a stable leader.

Rounds, Heights, Views and Levels

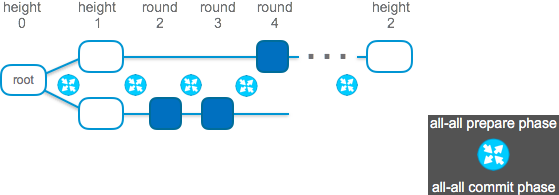

At a high level, TDRMNT (like PBFT) operates in a sequence of decisions. Each decision index is referred to as its “height”, representing the corresponding level of the blockchain.

Like PBFT, the protocol for deciding on the block at each height is view’ based, where each view has a dedicated proposer by rotation. In a view, one decision may be reached or none. In Tendermint, a view is called a round’. The view is changed if a certain period elapses without progress. When a decision is reached, the engine moves to the next height.

In summary, the overall framework of Tendermint consists of height-by-height decisions, and a multi-view protocol per height, as depicted here:

This paradigm is standard in the BFT literature, but is very confusing. We can considerably simplify it, because there is no reason to have two counters, one for heights, and one for rounds; and there is no reason to distinguish rounds with decisions from rounds without decisions.

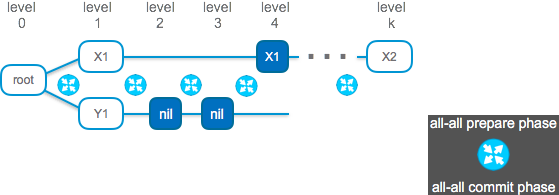

Using the HotStuff framework, we are going to blur in TDRMNT the distinction between heights and views, and use only `levels’. At each level, a proposer needs to choose a branch to extend. If there is no proposal at the preceding level, it regards it as a nil proposal. The proposer may decide to extend the branch with new content or to merely reinforce an undecided branch.

The scenario above has the following levels and proposals:

Voting and Locking

TDRMNT employs a two-phase voting approach that borrows from PBFT. It differs from PBFT in a locking/unlocking scheme that considerably simplifies proposer-replacement, but throttles the pipeline of proposals.

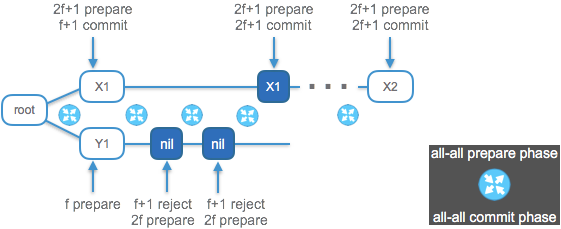

The two phases of voting are named a prepare’ phase and a commit’ phase. In each one, votes are broadcast in all-all exchanges among replicas over a gossip network. The goal of the prepare phase is to obtain 2f+1 prepare votes on a unique branch. When a replica obtains 2f+1 identical votes it is called a ‘polka’ in Tendermint, but we will refer to it as a `commit-certificate’ to link it with the classical PBFT foundations.

When a replica obtains a commit-certificate for the current level, it sends a commit-vote and becomes `locked’ on the branch with the commit-certificate. A decision will be reached when 2f+1 commit votes are placed on a commit certificate.

Once a replica in TDRMNT is locked on a branch, it may vote prepare on proposals that extend the branch to higher level, but not on a different branch. To prevent being “stuck” in a locked state, a locked replica may become unlocked and move to another branch if it receives a commit-certificate with a higher level than the one it is locked on.

To transition a level, each replica waits for 2f+1 (possibly nil) votes at each voting step before moving to the next step. A proposer does not send a proof, it simply extends the branch with the highest commit-certificate it knows. Each replica chooses if it can accept the proposal based on the highest commit-certificate it collected.

In this way, TDRMNT deals with a proposer-replacement as any level transition, making the proposer-replacement both simpler and more efficient than PBFT.

One consequence is that in TDRMNT, each replica must wait (twice) for 2f+1 votes to transition steps.

Safety

Unifying heights and views into a simple level-by-level protocol makes the safety argument in TDRMNT straight-forward.

If a decision is reached on a branch, then f+1 correct replicas will not vote on another branch unless they obtain a higher level commit-certificate for the conflicting branch. But such a higher-level certificate would involve at least one of these f+1 replicas. Therefore, a commit-certificate with a higher level for a conflicting branch requires a commit-certificate with a higher level for the branch, hence it cannot ever be formed.

Let’s revisit the scenario depicted above and speculate on the voting that might have transpired. 2f+1 replicas vote prepare and f+1 vote commit on X1. f other replicas vote prepare on a conflicting proposal Y1. These replicas might be slow or disconnected. They try to extend the Y`‘ branch with proposals Y2 and Y3. Another f replicas might even join them! But since f+1 good replicas are locked on theX‘ branch, only the X‘ branch may be extended with committed decisions. Eventually, at level 4 a good proposer reinforces X1, and all good replicas vote for it.

PBFT, TDRMNT, Casper and HotStuff

The key difference between PBFT and blockchain protocols like TDRMNT, Casper and HotStuff is the use of a locking mechanism to transition between levels. Locking makes the proposer-replacement protocol both simpler and more efficient. TDRMNT, Casper and HotStuff, all use the simple proposer-replacement regime, and differ in other algorithmic and complexity aspects.

Let’s first compare PBFT and TDRMNT. In PBFT, a new proposer collects view-change’ message from a quorum of 2f+1 containing their highest-level commit-certificates. It pushes these reports to replicas as proof of safety within anew-view’ message.

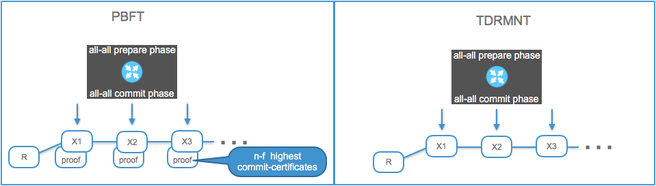

These differences are depicted here:

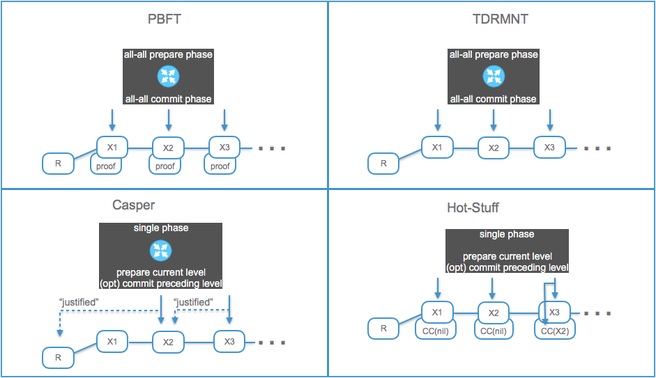

Next, let’s throw into the mix Casper and HotStuff.

Casper was inspired by Tendermint, and like TDRMNT, it relies on a gossip network to spread votes, and does not include a commit-certificate inside a proposal. Differently, it refers to a commit-certificate in the vote itself, hence a replica does not necessarily wait for a commit-certificate to move to the next level; a new level starts upon receiving a new PoW proposal. In this way, Casper has only a single vote type that consists of two parts, a prepare-vote on the current level, and an optional commit-vote on the preceding level. (In a previous post, I explain Casper in the lens of BFT.)

HotStuff is inspired by all three works, and strikes a middle-ground. On the one hand, unlike PBFT, a proposer in HotStuff does not collect view-change report or disseminates them them as proof of safety. On the other hand, a proposer in HotStuff does include in the proposal the highest-level commit-certificate it knows. There are several important benefits to this approach. One, HotStuff alleviates the need for all-all communication, thus reducing communication by factor n. Two, a proposer can combine signatures from multiple votes into one using threshold crypto, thus reducing communication and crypto overhead on the replicas by another factor n. Last, similar to Casper, including a commit-certificate within proposals simplifies voting, hence there is a single type of vote in HotStuff.

Below we depict the four paradigms, PBFT, TDRMNT, Casper and HotStuff, next to each other. All four follow the fundamental two-phase voting foundations established by PBFT. The first phase tries to obtain a commit-certificate (2f+1 prepare-votes) for a unique proposal. The second tries to reach a decision via 2f+1 commit-votes referring to the commit certificate. They differ in how commit-certificate information is transferred from level to level.

- In PBFT, a new proposer starts by collecting commit-certificates from 2f+1 replicas and using it as proof of safety.

- In TDRMNT, a replica starts each a new level (even with a stable proposer) by waiting for prepare and commit votes from 2f+1 replicas. It relies on the gossip network to spread votes among all replicas in both voting phases. A replica verifies a proposal safety against the highest-level commit-certificate it knows.

- Casper also relies on gossiping of votes, but a replica does not wait for 2f+1 votes at each level. Rather, a replica starts a new level upon a PoW proposal. Upon voting, a replica references a “justified” block, the highest level commit-certificate it has. This actually simplifies voting: Only one voting phase occurs per level.

- HotStuff also has a single, two-part vote but does not require all-all gossip. At each level, a proposer (optionally) collects a commit-certificate, and includes the certificate within the proposal.

Liveness

Liveness is guaranteed in TDRMNT under certain synchrony assumptions.

As in PBFT, liveness is provided in TDRMNT through proposer rotation. Although replicas progress from level to level independently, under timely communication conditions they regularly reach the same level and vote (twice) without any timer expirations. This suffices to guarantee liveness.

The conditions for triggering level transition in TDRMNT are as follows. A replica waits at a level twice, one time to collect 2f+1 prepare votes, and then again for 2f+1 commit votes. In both voting phases, if a timer expires, it votes nil.

Prepare-phase: At the beginning of level r, a replica waits to receive a proposal for a certain period. If it receives a (well-formed) proposal from the designated proposer for the level before the timer expires, then it sends a prepare-vote on it. Otherwise, if the timer expires before receiving a proposal for level r, a replica sends a prepare-vote for nil.

A replica then waits to receive 2f+1 prepare-votes for a period. As a matter of practical optimization, if it receives 2f+1 mixed prepare-votes, some on a proposal, others on nil, it extends timer with extra time.

If a replica receives a commit-certificate before the timer expires, then it sends a commit vote on it. Otherwise, if the timer expires before receiving a commit-certificate for level r, the replica sends a commit for nil.

Commit-phase: A replica then waits to receive 2f+1 commit votes for a period. If a replica receives 2f+1 commit votes on a proposal before the timer expires, then it outputs a decision and then moves to the next level. Again, as a matter of practical optimization, if a replica receives 2f+1 mixed commits, some on a proposal, others on nil, it extends the timer with extra time.

If the timer expires before receiving 2f+1 identical commits for level r, the replica moves to level r+1 without a decision.

Given the level transition mechanism above, we can articulate sufficient conditions for liveness.

To make progress at a level, 2f+1 replicas must enter the level at approximately the same time, vote (twice), and receive each other’s votes. Since in order to enter a level, a replica waits for 2f+1 commit messages at the previous level, it suffices that messages arrive to all replicas within a certain bounded delay. To guarantee this, TDRMNT relies on reliable and timely gossip communication of all messages, including ones from Byzantine sources. The reliable gossip protocol in TDRMNT can provide this guarantee provided that the underlying network communication is timely.

Additionally, the timers set for a level must allow sufficient time for delivery of votes. For example, assuming all messages arrive within delay D to all correct replicas, they will enter a new level within period D of one another. Setting level-timers to at least 2D, replicas can guarantee to collect the same sets of votes and drive progress.

To recap, two synchrony conditions suffice for TDRMNT to have liveness: Reliable synchronous broadcast communication, and setting expiration timers accordingly.

Take-Aways

TDRMNT is a BFT solution that borrows from the Tendermint write-ups as best I could, and cast into the unifying framework of HotStuff.

- Safety and liveness: HotStuff can be utilized to reason about TDRMNT, provide a simple argument of TDRMNT safety, and express rigorous conditions for its liveness.

- Algorithmic complexity compared with PBFT: TDRMNT is different. A stable proposer must operate on one level at a time. The communication complexity in case of a stable proposer is the same, two all-all exchanges. The protocol for replacing a proposer is considerably simpler in TDRMNT and has reduced communication complexity compared with PBFT.

- Comparison with Casper and HotStuff: Casper relies on an auxiliary mechanism (PoW chain) to prevent spurious level-transitions, not on the BFT protocol itself. Casper further simplifies the voting protocol to consist of one voting phase only. HotStuff offers a general framework, and a specific implementation with a rotating proposer that improves communication complexity by O(n).