What They Did not Teach you in Streamlet

Authors: Shir Cohen and Dahlia Malkhi

In an ePrint article and a following post, Chan and Shi introduce Streamlet, a “textbook blockchain protocol” that is “absurdly simple, making it a perfect choice for pedagogy”.

In this post, we explore the gaps Streamlet leaves, including:

-

Streamlet incurs n3 message complexity per block.

-

Reducing the communication complexity is far from trivial.

-

Streamlet makes a strong and unnecessary synchrony assumption.

-

Streamlet does not provide API for State-Machine-Replication.

To close these gaps, we indicate below how to convert Streamlet to HotStuff. Given the striking similarity Streamlet bears to HotStuff, this is done in a few easy steps. In doing this, we aim to preserve the benefits of pedagogy and bring the benefit of an engineering-ready BFT consensus.

A Quick overview of Streamlet

Model: Streamlet is a protocol for the partially synchronous and authenticated settings. The system consists of n=3f+1 known validators, up to f of which may be Byzantine and the rest are honest. The network has an unknown global stabilization time (GST), after which there is a known duration Δ (measured in units called rounds) that bounds all transmission delays between honest validators.

Blocks and Notarization: Streamlet is an epoch-by-epoch protocol with a known designated leader per epoch. In each epoch a leader broadcasts a proposed block carrying transactions, and a hash of the prefix of the extended chain. Once a validator observes 2f+1 votes per block (quorum certificate) it considers this block notarized.

Longest Chain and Casting Votes: Every honest validator maintains the longest notarized chain(s) that it knows.

-

A leader proposal extends its longest notarized chain, or an arbitrary one of them if there are more than one

-

A validator votes for a leader proposal iff it extends one of its longest notarized chains, and the epoch number of the block matches the current epoch

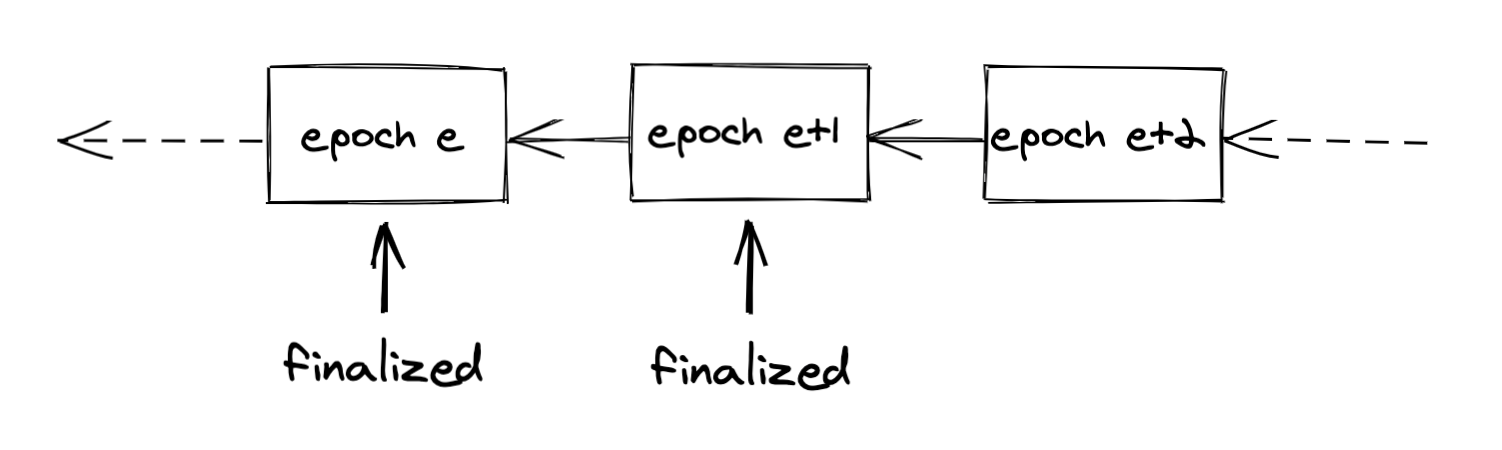

Commit: Whenever a 3-chain of notarized blocks (as depicted below) whose epochs are consecutive is formed, a validator finalizes the middle block of the 3-chain and its prefix chain.

Echo: In Streamlet, every validator must echo every message it receives to all other validators. Skipping the echo mechanism violates the liveness property of the protocol, even in perfect synchrony.

Epoch synchronization: Streamlet requires epochs to start in perfect synchrony and to last 2Δ rounds. Under this assumption, Streamlet guarantees a new finalization after GST whenever a succession of 5 epochs with honest leaders occurs.

Morphing Streamlet back into HotStuff

Turning Streamlet into HotStuff is trivial, because Streamlet is built with the same ingredients of HotStuff – blocks, designated leaders, quorum certificates (QCs), and a 3-chain finality rule. In HotStuff, a block is linked to its parent using the QC itself, on-chain, so everyone can verify it has been notarized.

HotStuff highest QC: In HotStuff, every validator keeps the highest epoch QC (HighQC) it knows of, instead of a block itself as in Streamlet.

As in Streamlet:

-

A leader proposal extends highQC.

-

A validator votes for a leader proposal if it extends the branch of its highQC.

HotStuff commit:

Whenever a 3-chain of alternating blocks/QCs whose epochs are consecutive is formed, the middle block of the 3-chain becomes finalized.

HotStuff round synchronization:

HotStuff does not require epoch synchronization for safety. Rather, it has a component called PaceMaker for advancing epochs that guarantees progress. PaceMaker advertises the start of an epoch in order to bring non-faulty validators to overlap in the same epoch during periods of network stability. See additional discussion below.

**That’s it! **

Streamlet has high communication complexity

In each Streamlet epoch, every validator broadcasts the votes of all other validators which sums up to n³ messages per epoch, even in the case of an honest leader. It is known from Dolev and Reicschuk that the lower bound for an instance of Byzantine agreement is O(nf) signatures. If, however, we restrict ourselves to the case of an honest leader, we still must use \Omega(n) messages to spread the value among all validators. Previous work in this field has already exposed better performance than Streamlet. For example, HotStuff has communication complexity of O(n) in epochs with honest leaders, and O(nf) in the general case.

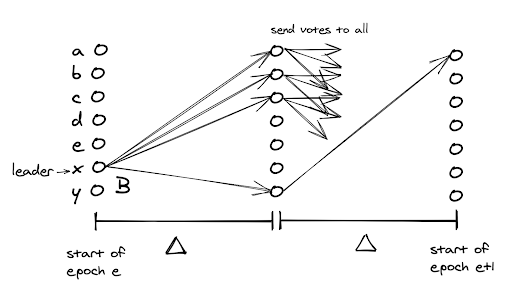

Importantly, Streamlet does not work without echoing messages (incurring n3 communication complexity). Here’s a simple example to explain this (appears in the figure below): Assume a system of 7 validators {a,b,c,d,e,x,y} where validators x and y are Byzantine. By epoch e, all honest validators share the same view of the world. Then, x is chosen to be the leader of epoch e. During the first round of epoch e (Δ) it sends its block proposal B only to validators a,b,c and y. In the following round, a,b and c, follow the protocol and vote for the proposed block, sending their signature to all other validators. y, on the other hand, sends its vote only to a. At this point the epoch ends and no further votes on the block are casted. It is clear that at this point a has collected 5 (=2f+1) votes for the proposed block (from a,b,c,x,y) while any other honest validator collected only 4 of them. This leads to the proposed blocked being notarized only by a.

If there are no vote echoes, in the following epochs a does not vote for any proposal that doesn’t extend B. If the Byzatine cease to participate, liveness is compromised. When a becomes leader, it proposes to extend B and no one else votes for it, because they don’t know it is notarized.

Streamlet requires lock-step epoch synchronization

Streamlet is designed for the partial synchrony model, where it is possible to eventually achieve bounded clock skew. However, it makes a strong and unnecessary requirement that epochs operate in lock-step. Therefore, whereas Streamlet resembles HotStuff with its simple 3-chain commit rule, it foregoes a pinnacle of asynchronous consensus protocols: the ability to advance at the speed of the network without waiting maximal network delays.

In HotStuff as in other BFT protocols for the partial synchrony settings, it is known that in order to guarantee progress honest parties must be brought to overlap in epochs for sufficiently long. This enables honest leaders to obtain QC’s for their proposals. However, there is no need to require that rounds occur in perfect synchrony as in Streamlet. Several scholarly works deal with logical epoch synchronization:

-

PBFT uses epoch-doubling to provide progress in the partial synchrony model.

-

HotStuff introduces an abstraction called PaceMaker that captures the requirements of Byzantine round synchronization in BFT consensus.

-

Cogsworth explores latency/communication tradeoffs in PaceMaker implementations ([video], [https://arxiv.org/abs/1909.05204]).

-

Cogsworth bounds are further tightened in [https://arxiv.org/abs/2002.07539].

-

Treshold Logical Clocks generalizes PaceMakers to other of Byzantine protocols.

Streamlet does not provide API for SMR

In Streamlet, QCs are not recorded on the blockchain itself. That is, once a validator in Streamlet observes 2f+1 votes for a block (quorum certificate), it considers this block notarized. However, unlike Hotstuff, Streamlet leaders do not embed QCs within proposed blocks. Therefore, while Streamlet creates a total-order on client requests, the question of how an external client can verify the correctness of the log and obtain a response is not addressed. Blockchains and State Machine Replication (SMR) are used to serve clients, and clients need to be able to query the service to obtain the latest state.

This gap is easy to resolve by storing QCs on the blockchain (as in hotStuff). Another simple option is for client queries to collect responses from a read quorum.

Summary

Streamlet is “absurdly simple”, though perhaps too simple, as it leaves gaps for the reader to fill. This post underscores several gaps and indicates how related literatures solves them around message echoing, communication complexity, synchronization, latency, and the SMR service.