Flexible Paxos

Summer was buzzing with intern activity at the VMware Research Group (VRG), working with all the research team and with David Tennenhouse, Chief Research Officer of VMware, and Chris Ramming, director of XLR8 and VMAP. Here I chose to share one story from our productive summer.

Early in the summer one of the interns, a Cambridge UK student of Jon Crowcroft named Heidi Howard, approached me with a surprising observation about Paxos:

Each of the phases of Paxos may use non-intersecting quorums. Only quorums from different phases are required to intersect. Majority quorums are not necessary as intersection is required only across phases.

Everyone in the field of distributed systems knows that quorums in Paxos must intersect. So, what gives?

“The most useful piece of learning for the uses of life is to unlearn what is untrue. ”

Antisthenes

Let me backtrack and describe what we are talking about.

Distributed consensus is the problem of reaching agreement in the face of failures. It is a common problem in modern distributed systems and its applications range from distributed locking and atomic broadcast to strongly consistent key value stores and state machine replication. Lamport’s Paxos algorithm is one such solution to this problem and since its publication it has been widely built upon in teaching, research and practice.

At its core, Paxos uses two phases, each requires agreement from a subset of participants (known as a quorum) to proceed. The safety and liveness of Paxos is based on the guarantee that any two quorums will intersect. To satisfy this requirement, quorums are typically composed of any majority from a fixed set of participants, although other quorum schemes have been proposed.

In practice, we usually wish to reach agreement over a sequence of values, known as Multi-Paxos. We use the first phase of Paxos to establish one participant as a and the second phase of Paxos to propose a series of values. To commit a value, the leader must always communicate with at least a quorum of participants and wait for them to accept the value. For a brief history of the developments that led to Paxos, see Lamport’s ACM tribute page .

What Heidi observed is that Paxos, which lies at the foundation of many production systems, is conservative. Within each of the phases of Paxos, it is safe to use disjoint quorums and majority quorums are not necessary.

Jointly with another intern, Sasha Spiegelman, a Technion PhD student of Idit Keidar, we proceeded to weaken the requirement in the original protocol that all quorums intersect to require only that quorums from different phases intersect. Using this weakening of the requirements made in the original formulation of Paxos, we propose Flexible Paxos, which generalizes over the Paxos algorithm to provide flexible quorums.

We posted a manuscript to the ArXiv (URL: https://arxiv.org/abs/1608.06696). Heidi posted a nice blogpost about it, and later, the paper has been accepted for publication at OPODIS 2016 (see [pdf]). In the paper, we showed that Flexible Paxos is safe, efficient and easy to utilize in existing distributed systems.

There are far reaching implications of this result.

Since the second phase of Paxos (replication) is far more common than the first phase (leader election), we can use FPaxos to reduce the size of commonly used second phase quorums. For example, in a system of 10 nodes, we can safely allow any set of only 3 nodes to participate in replication, provided that we require 8 nodes to participate when recovering from leader failure. This strategy, decreasing phase 2 quorums at the cost of increasing phase 1 quorums, is referred to in the body of the paper as “simple quorums”.

The simple quorum system reduces latency, as leaders will no longer be required to wait for a majority of participants to accept proposals. Likewise, it improves steady state throughput as disjoint sets of participants can now accept proposals, enabling better utilization of participants and decreased network load.

Usually, the price we pay for this is reduced availability as the system can tolerate fewer failures whilst recovering from leader failure. Surprisingly, there is a specific case of simple quorums where the is no cost at all: reducing the size of second phase quorums by one when the number of acceptors is even. This improves the performance and availability of steady-state phase 2, without hurting availability of phase 1. In the above system of 10 nodes, you would use sets of size 5 to form phase 2 quorums, and sets of 6 to form phase 1 quorums.

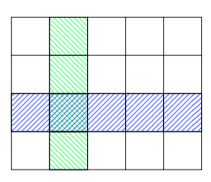

In the paper, we additionally illustrate that there are quorum systems such as grid quorums, in which FPaxos allows to decrease the quorum sizes of both phases. Furthermore, in this quorum system, the quorums within either phase do not intersect with each other. The figure below shows the FPaxos grid quorum, with every column forming a phase 1 quorum, and every row a phase 2 quorum.

In summary, by no longer requiring replication quorums to intersect, we have removed an important limit on scalability. Through smart quorum construction and pragmatic system design, we believe a new breed of scalable, resilient and performant consensus algorithms is now possible. For more details, see our manuscript [ArXiv link].

The summer is nearing its end, and brings to a close an incredible amount of innovation and results from the VRG research interns. I will not attempt to list all projects and accomplishment because if I try to list them all, I will surely cause un-justice. Stay tuned for the publications and continued research projects from this summer!